Historians offer first impressions of Pius XII archives

Archives of the World War II-era pontificate were opened only five days before coronavirus forced Vatican's temporary closure

22/05/2020 | Na stronie od 22/05/2020

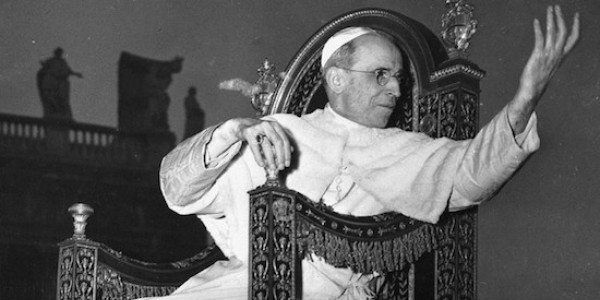

The archives underline how well informed the Vatican was about the situation in Europe, even though not all the information was necessarily going back to Rome. (Photo by STRINGER/AFP)

Nicolas Senèze Vatican City

The Vatican Apostolic Archive finally opened its files on the pontificate of Pope Pius XII (1939-1958) on March 2, but just five days later it was forced to close because of the COVID-19 crisis.

"The global pandemic has allowed time for more meticulous daily research," says historian Nina Valbousquet, in a fascinating article in the online magazine Entre-Temps.

A researcher from the "École française de Rome", she specializes in relations between Judaism and the Church. During the lockdown she's had time to learn a little more about how the Vatican functioned during the Second World War.

Valbousquet discovered that, at the time, the Vatican was anything but a monolithic bloc dominated by the pope.

"Dilemmas" and "silence"

"The Church was already complex and international," says Andrea Riccardi.

The Italian historian and founder of the Sant'Egidio Community assessed his own early research into the Pius XII era archives in an article in the May 13 issue of the Milan-based daily, Corriere della Sera.

Valbousquet says a good example of the Church's diversity is seen, for example, in the archives of the Vatican nunciature in Paris, which had been moved to Vichy.

We see that the nuncio at the time, Archbishop Valerio Valeri, noted the "brutality" of the Vel d'Hiv Roundup of Jews in Paris in 1942, while also deploring the very "platonic" protest of the French bishops.

And there's a report on public opinion in the free zone in which the Jesuit Roger Braun said it was "astonishing and almost a scandal to see the hierarchy - and even Rome - remaining silent".

On the other hand, there's a letter that a priest from Marseilles sent to Pierre Laval (head of the Vichy government), with copy to the nuncio, in which he expressed indignation in violent anti-Semitic terms that his bishop had been publicly criticized.

The diversity of this information coming from all over Europe undoubtedly explains what Italian historian Giovanni Miccoli had called, as early as 2000, the "dilemmas" of Pius XII, as much as his "silences".

Riccardi insists that such a plurality of information is crucial to understanding what really happened. He points out that from the beginning of the war, Pius XII was worried about how his silence about Poland would be perceived.

A "center for information"

"During the Second World War, the Church was won over by the divisions caused by war propaganda in Poland. The Nazis put forward a pope aligned with Germany, generating an impression of abandonment by Polish Catholics," Riccardi says, stressing that the Vatican was not in a strong position at the time.

"The power of the Church was, therefore, a myth. The Holy See in the 1940s was a handful of men surrounded by Nazis," he insists.

"You can really wonder how much room the Holy See had for maneuvering," Valbousquet says in agreement.

Nevertheless, she says the Vatican was able to offset its weakness by becoming a "center for information".

The archives of the apostolic delegation in Jerusalem show how the Vatican representation became a letterbox between the Jews of Palestine and those who remained under the boot of the Reich.

"I was impressed by this role of intermediary which began very early, from 1940-1941," she told La Croix.

The historian also looked at the series of files, "aid and assistance to refugees on grounds of race or religion", which was begun under Pius XI and "grew considerably under the pontificate of Pius XII".

This is a sign of real humanitarian action even if the Vatican did not seem to want to give up its neutrality.

"A slow awakening"

The archives underscore how well informed the Vatican was about the situation in Europe, even though not all the information was necessarily sent to Rome.

For example, Riccardi's article in Corriere della Serawas published alongside photos found in the apostolic nunciature in Switzerland. They show naked Jews just before being executed, with a terrified look in their eyes. They also show German soldiers burying corpses.

"News was pouring into the Vatican, although it was not always easy to verify. It cannot be said that the pope was not aware of the massacres of the Jews, as his defenders sometimes have claimed," Riccardi says.

"At the beginning of the war, the Holy See considered that each side had its faults -- both the Nazis and the Communists," Valbousquet says.

"Pius XII did not want to condemn the Nazis without mentioning the Bolsheviks," Riccardi adds.

"But he was also aware that, once the war was over, Hitler would put an end to the Church. So the pope, for instance, forced American Catholics to support Roosevelt's aid to the Soviets," the Italian historian says.

"Looking at the archives one can see an evolution: we feel that, as the information was coming in, there was a growing awareness, even if it was slow," insists Valbousquet.

She hopes to resume her research on June 1. That's when the Vatican Apostolic Archive reopens its doors -- but for only 15 researchers.