In age of #MeToo and cancel culture, medieval philosopher’s ideas can heal wounds

How Maimonides’s five steps for repentance can fix the serious harm done by individuals and institutions in contemporary America

25/09/2022 | Na stronie od 25/09/2022

Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg (Sally Blood)

Source: The Times of Israel

By RENEE GHERT-ZAND 25 September 2022

Have you hurt someone? Have you caused them harm? Just saying sorry — even if you mean it — won’t cut it and Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg is here to make things right.

The activist rabbi believes that American culture is broken when it comes to doing repentance and repair. Private individuals, public figures, institutions, organizations, and the country as a whole all do harm. But almost no one knows what to do to really make things right for both the victim and the perpetrator.

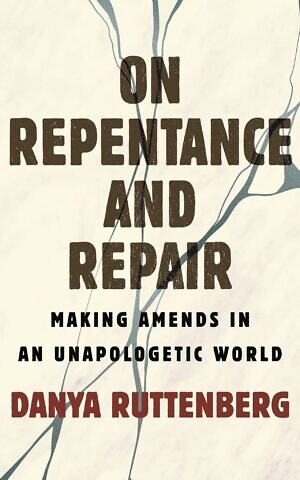

Published on September 13, Ruttenberg’s new book, “On Repentance and Repair: Making Amends in an Unapologetic World,” offers Americans and others a tried-and-true Jewish model for repentance. In the book, Ruttenberg illustrates how the laws of repentance conceived by medieval Jewish philosopher Rabbi Moses ben Maimon (also known as Maimonides or Rambam) — if properly applied — could rectify much of what isn’t working in society and alleviate a lot of the pain felt by those who have been harmed in different ways.

“It’s not that nobody has come up with other systems of accountability, but I think Rambam’s steps work and I don’t see any reason why we can’t share them out with everybody,” Ruttenberg said in an interview with The Times of Israel from her home in the Chicago area.

According to Ruttenberg, there are many reasons why the hard work of repentance doesn’t come naturally for America and Americans. Among them are the generations-born traditions of rugged individualism and hyper-capitalism.

‘On Repentance and Repair: Making Amends in an Unapologetic World’ by Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg (Beacon Press)

Ruttenberg, scholar in residence at the National Council of Jewish Women, also points to “a salient thread long woven into our national fabric of thinking about repentance as a watered-down, secularized distortion of Protestant thinking that has infused the culture.” This is the idea that God’s forgiveness is available to all those who believe, whether or not they take action to make repairs and restitution and to truly transform themselves. This attitude has played out repeatedly in American history when justice was sacrificed for the sake of keeping the peace and moving the country forward without reckoning with the past.

Maimonides’s laws of repentance (teshuva in Hebrew) amount to a five-step program that demands strict and comprehensive adherence. There are no skipping steps and no cutting corners. There is also no maximum time limit for each step. You need to stick with each until you have robustly completed it.

The steps (in Ruttenberg’s terminology) are: 1) Naming and owning harm; 2) Starting to change; 3) Restitution and accepting consequences; 4) Apology; and 5) Making different choices.

Ordained by the Conservative movement, Ruttenberg, 47, cites the biblical and rabbinic sources that undergird this model, and applies it to contemporary case studies ranging from sexual abuse by public figures, to penal incarceration policies, to medical malpractice lawsuits, to the Holocaust and other genocides.

The following is an edited version of The Times of Israel’s conversation with Ruttenberg.

What was the impetus for the book?

When #MeToo broke, a friend of mine was writing a piece… about all of these men who were outed as abusers. There was this void in the cultural conversation. People were asking — what now? What do we do with these guys? When do we know when they come can back? What does repentance look like? People were really confused.

My friend asked me for a quote for their piece and I wrote up a couple of paragraphs based on Maimonides and sent it in. My friend used a sentence or two, but after the piece came out I decided to tweet everything I had given them. I distinguished between repentance, forgiveness, and atonement. I briefly explained Rambam in the context of these larger cultural conversations of what it means when someone who is very public does harm and there are all these witnesses and bystanders.

People went bananas. People had never seen anything like this. That is, putting the heaviest labor of repentance on the harm doer, and that there are specific things that they need to do, and specific things we can look for to know if they have done the repentance.

The tweet thread led to some op-eds, which eventually led to this book.

In the book, you use many examples and cases, traditional Jewish sources, and quotes from academics and activists. You also infuse the book with your own style and voice. How did it all come together in a way that would resonate with Jewish and non-Jewish readers?

Maimonides marble bas-relief in the chamber of the US House of Representatives in the United States Capitol (Public Domain)

I knew that I wanted to be talking about the work of repentance on the individual level, institutional level, and national level. It just became a case of finding the right stories and examples to illuminate that.

In a lot of ways, the right stories found me. I spent a lot of time looking and talking to people. I read books, blog posts, and essays. Sometimes I would hear things through a friend of a friend. There were a lot of possible stories to include, and these were the right ones. There was a lot of historical research and interviewing scholars to have my i’s dotted and my t’s crossed. I had a lot of sensitivity readers — mostly Black and native women.

You use a lot of terms that people are prone to confuse or conflate — repentance, forgiveness, repair, transformation, atonement, confessions, and apology. Why is it important to define each carefully and not mix them up?

If we don’t understand what repentance is, what forgiveness is, and what atonement is, then when harm happens, we don’t know what to do. We don’t know who is obligated to do what. When someone is sitting there hurt and needing care, we don’t know what we are supposed to ask of them or not, what we are supposed to give them or not. The harm doer doesn’t know the nature and limits of their obligations.

What concept confuses people the most?

It is an aha! moment for people when they learn that repentance and forgiveness are different tracks. You can do all the work of teshuva and never be forgiven by the person you hurt. If you do sincere, thoughtful, and meaningful repentance but are still not forgiven, you may go to God and get atonement on Yom Kippur.

Forgiveness is its own process and the person who was harmed has their own healing and their own relationship with the divine, themselves, and the person who harmed them. It’s their business.

In our culture, repentance and forgiveness have been so deeply intertwined and tangled up that for people to understand that they are separate tracks is a revelation. It is so freeing, particularly for people who have been harmed, who often feel coerced into forgiving. If we are not clear and precise in our language, then people wind up not fully knowing what they are doing. The emotional weight of that is really heavy.

You emphasize that it is okay for a victim to never forgive the perpetrator. That goes against Maimonides, who says that not forgiving is a sin.

I disagree with him on this specific point. In some ways it’s radical to question Rambam, but it’s okay. I am comfortable as a rabbi who has come into own her voice, as someone who believes every generation receives the Torah anew, as someone who reads Torah with a feminist lens and understands that there a lot of things historically in Judaism that we have to look at carefully. Rambam cited Midrash (a non-legal source) saying that not forgiving is a sin. I was careful to bring much more authoritative textual sources to show the opposite.

You devote an entire chapter to justice systems, with an emphasis on restorative justice work as an alternative to current systems. Why?

We can’t talk about harm if we don’t talk about the consequences for doing harm. If we are talking about serious, significant harm and that accepting the consequences of it is part of the repentance process, we need to ask what this means… If consequences make it impossible for repentance to take place, we need to reckon with that.

The way our society currently [determines and administers consequences] makes it impossible for perpetrators to do real repentance work. If we want to create a more whole society where people can actually repair their harms, and if we care about actually serving victims, then the system we have doesn’t work.

What makes you optimistic that Rambam’s laws of repentance can work for American society, and what makes you pessimistic?

What makes me optimistic is the response I have gotten every time I have talked about this stuff and how hungry so many people are for a real significant, robust model of repair and accountability that can transform lives and institutions, and our culture. We’ve seen scandal after scandal rocking institutions, and people are seeing that there is a penalty to that and that there are incentives to getting it right. I have done some consulting work with organizations that are struggling with their teshuva process. People are taking it seriously. This gives me hope.

What gives me less hope is that power does not give up power easily. If done right, some of this work may demand paradigm shifts in how power exists and functions, and that is real. Particularly given the state of American culture today. There is a lot of work to do as we think about naming harm and accountability for harm, and some of those in power have worked hard to not do that.

A prison guard is seen in a watchtower at Gilboa prison, in northern Israel, September 6, 2021. (Flash90)

What is the main message you want readers to take away from this book as we approach the Ten Days of Repentance on the Jewish calendar?

The work of teshuva, of coming back to who you are and who you are supposed to be in relationship to yourself and the divine is hard. It is humbling. It requires crossing that bridge from the story you tell yourself where you are always the good guy and the hero over into the place where you see what truly is. That is the hardest cognitive dissonant gulf to cross.

To be able to leave the ego behind and move over into the place of naming what is true is such a profound act of caring for others, of giving love and healing to those you have hurt. And doing the work of repentance and repair not only cares for them but transforms you in ways you didn’t even know you needed. If you can cross that bridge, it is all there for you.